|

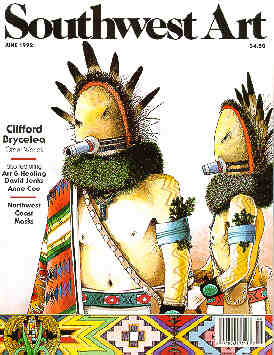

Clifford Brycelea had set his mind on a master s degree in commercial art

... or so he thought in 1976. That was before his mystical paintings of

southwestern Indian culture began selling like hotcakes. Before he met

up with western novelist Louis L Amour. Before, in short, Brycelea realized

he already had a career in art.

Clifford Brycelea had set his mind on a master s degree in commercial art

... or so he thought in 1976. That was before his mystical paintings of

southwestern Indian culture began selling like hotcakes. Before he met

up with western novelist Louis L Amour. Before, in short, Brycelea realized

he already had a career in art.

Today, Brycelea s subject

matter is as varied as the many media he uses. Yet a mystical thread remains

strong in his work, especially in his landscapes. Executed in deep browns,

eerie ochres or slightly surreal greens, they seem to repeat an ancient

ceremonial chant: "It all returns and ends in the land." Remote hogans,

solitary tipis, bare trees and shadowy birds ostensibly hearken back to

the old days. In fact, however, they carry an urgent message for the present.

"If you study my paintings,

you ll see they relate to our Mother Earth," says Brycelea [pronounced

Brice-lee]. "The environment s like anything else. You have to read the

instructions or you ll break the thing." Brycelea (Az 1953—LIVING NM) learned

his ecology among the pinons and junipers of the Lukachukai Mountains on

the Navajo Reservation near Cove, AZ. His traditional upbringing included

a boarding school education that began when he was 5 years old. In second

grade he remembers doing two drawings on the opposite sides of a sheet

of paper: One he liked and one his teacher liked. The latter drawing won

first place at the Northern Navajo Fair in Shiprock, NM, and from

the experience, Brycelea absorbed an invaluable lesson: Artists aren't

the best judges of their own work.

Brycelea forgot about art

until high school at Fort Wingate where he took a class in oil painting

... which he almost flunked. "I couldn't do anything with oil, I was a

total wreck," he chuckles. But his drafting skills were popular with his

classmates, who pestered him for pencil and pen-and-ink drawings for the

yearbook. Then, while leafing through Arizona Highways, Brycelea discovered

another level of illustration in the works of Robert Draper, Jimmie

Abeyta and Harrison Begay [SWA JUN 821. Begay s work especially intrigued

the young high-school student. "His images were strong, like dreaming something

and making it real." Another source of inspiration was his uncle Harry

Walters, an artist, art instructor and past director of the Navajo Ceremonial

Museum (now the Wheelwright Museum, Santa Fe, NM).

Nonetheless, Brycelea was

leaning towards trade school rather than college when he met with his high-school

guidance counselor to map out his future. She discouraged Brycelea from

pursuing higher education, telling him that athletes might make it through

college, but he wouldn't. That s when Brycelea resolved to prove her wrong.

Enrolling at Fort Lewis College

in Durango, CO, Brycelea was exposed to a

bewildering variety of art

classes. One of his principal instructors was Mick Reber, who specialized

in commercial art. "I still use that commercial approach today," explains

Brycelea. Strong horizon lines and perpendiculars predominate in his work,

as do eye-directing curves and diagonals. These, combined with his compositional

economy, make his paintings easily adapted for use as illustrations.

While in college, Brycelea

s subject matter reflected other-worldly concerns of a type that might

surprise his present collectors: spaceships and aliens, for example. It

was only after graduating from Fort Lewis in 1975 that he tried his hand

at Indian images. Finishing a group of watercolors, he took them to the

Jackson David Trading Company in Durango, CO. Owner Jackson Clark specialized

in Indian jewelry and rugs and was just beginning to expand into the visual

arts. In a sense, the two men learned the art business together. Clark

took Brycelea s paintings on the road with his other inventory and when

he found he couldn't field questions about them, he invited Brycelea to

accompany him.

"We taught each other," observes

the painter."We talked to other artists, picked up marketing tips and went

from there." Clark encouraged Brycelea to enter his work in competitive

shows and within a year he started turning up ribbons and purchase awards.

Still planning to return to school for a master s degree, Brycelea was

sidetracked by western writer Louis L Amour, who purchased his first Brycelea

painting in 1977.

L Amour was living in Beverly

Hills, CA, at the time but he d come to Durango and stay at Tamarron ski

resort while researching his novels. When he went downtown he d stop at

the Trading Company. Recalls Brycelea, "Jackson Clark introduced us and

we just evolved into close friends."

The painting that caught

L Amour s attention was of a kneeling man in a kachina mask, above whose

head floated an ancient-looking design. That design— remote yet challenging,

seemingly capable of good or evil—would be perfect for his yet-unfinished

novel titled Haunted Mesa. The subject of the novel was the mysterious

Anasazi who vanished from the Four Corners region sometime around the thirteenth

century. Brycelea, who was similarly fascinated with the Ancient Ones,

often depicted their vacant cliff dwellings in his art. When L Amour learned

that Brycelea planned to stop painting and return to school, he invited

the young artist to dinner. "He saw something in my work and in me," recalls

Brycelea. "He thought I should continue in art."

The novelist backed his encouragement

with action, arranging a private showing for the artist at his Beverly

Hills home in 1981. L Amour would subsequently use Brycelea images to illustrate

two short stories as well as the novel Haunted Mesa, published in 1988.

Brycelea contributed more to the novel than its book jacket, however. He

shared with the writer some of the Navajo beliefs that inform its plot

and served as a model for one of the book s characters.

Although Brycelea left Durango

for Cove, and then Dulce, NM, he and L Amour remained close friends till

the author s death in 1988. L Amour collected Brycelea s watercolor landscapes.

Their bare-bones scenery and idyllic remoteness seemed, like L Amour s

novels, to praise the untrammeled spaces of the West.

"With the world as crowded

as it is today, I try to use a lot of space in my work," Brycelea explains.

"I want to create the kind of place where you feel you could go to relax

and no one would bother you."

SUMMER RAIN is a good example.

Though a bit more elaborate in composition than most of his landscapes,

the tranquility of the land and the inviting shapes of the sienna-colored

hogans convey the mystery and intensity of a sudden desert cloudburst.

Brycelea s landscapes are above all private places where the mind and eye

can rest free from sensory overload. At the same time there is a poignant

quality to these paintings, a warning that the physical equivalents of

these landscapes may soon go the way of the dinosaurs. Notes the artist,

"You might see a pine tree in my work—it will be halfway green but the

rest of the way to the top it s dried up." Indeed, all these images are

colored by a certain ambivalence. Birds generally evoke associations of

freedom for Brycelea but their dark silhouettes, few in number, foreshadow

another concern. "You hear on the news how people are killing eagles and

other birds. Someday all that ll be left will be scavengers."

The small scale of the landscapes

arose partly out of necessity. "I started doing miniatures in 1985 when

I was traveling from one show to another," he says. With but three weeks

in between these weekend stands, Brycelea found he could create miniatures

despite road distractions. And, as it turned out, the small size strengthened

the impression of intimacy he sought to create.

Brycelea still avoids oil

paints, preferring watercolors and acrylics for his landscapes and southwestern

Indian subjects and pen-and-ink for whatever strikes his fancy. The success

of this approach may be gauged, among other things, by the four gold medals

he has earned thus far from the American Indian and Cowboy Artists group

with whom he shows in their annual April exhibition. And by the title Brycelea

won in 1987 of "Indian Artist of the Year" from the Indian Arts and Crafts

Association. In fact, 1987 was a banner year for Brycelea—in addition to

the Haunted Mesa book jacket, his illustrations also appeared in Pieces

of White Shell by Terry Tempest which was named the Southwest Book of the

Year.

In 1988, after a three-year

hiatus, Brycelea experimented with returning to his mythic painting theme

in Putting Up The Stars. The response was overwhelming. "Customers called

me and came by, saying that they remembered me for that style." Approaching

his ceremonial subjects with care, Brycelea places sand painting figures,

for example, anywhere in the image except on the ground. That might offend

his Navajo viewers. On the other hand, he feels free to exercise his creative

imagination by combining Navajo stories with myths or motifs from other

southwestern tribes.

It was the Anasazi

he thought of when painting PUTTING UP THE STARS.

"At one time, the sky was

completely dark," relates Brycelea. "People wanted something to light it

up, just a little bit, so they asked the spirit people to help them." Brycelea

depicts his Shooting Star Kachinas atop a kiva located in thin air. Their

elaborate masks and glowing body paint emphasize their supernatural powers.

The kachinas hold black bowls from which the stars shoot in all directions

like fireworks, while one kneeling spirit records their placement in the

sky. The dazzling paths of the stars, the mysterious grandeur of the kiva

and the aerial view of the river all enhance the ethereal effect of the

image.

It was this range of subject

matter that won Brycelea his IACA title, presented, appropriately enough,

by Jackson Clark II. In 1981, the Durango trading company evolved into

Toh-Atin Gallery and a second generation of Clarks now handle Brycelea

s art. His gallery connections have proven crucial in another area too.

He met his wife, Edie, in 1987 while dealing with her mother, a Georgia

gallery and gift-shop owner.

The couple and their three

children live in Santa Fe, where Brycelea had a booth at the annual August

Indian Market since 1980. In 1991 Brycelea scored a coup when his acrylic

painting won the mayor s poster contest in Santa Fe. GOLDEN REELECTION

shows the familiar St. Francis Cathedral reflected in melting snow puddles

viewed from the Terraza Restaurant—an unusual twist on a beloved landmark

that won him 830 out of 900 possible voting points. Such overwhelming approval

has given Brycelea the confidence to continue in fine art ... a career

he gave himself a mere five to seven years to establish himself in. He

s beaten his self imposed deadline, but should he decide to pursue his

master s degree, he takes a tongue-in-cheek comfort in the fact that his

transcript is registered at the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena,

CA. "To this day," Clifford Brycelea says with a laugh, "all I have to

do is show up and register." SWA

|